It’s a hot topic in all circles involving agriculture: pesticides. Some are for, some are against, but in truth, most people simply don’t know that much about them. The term pesticide is actually a bit of a catch-all, and is often used interchangeably with herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and rodenticides, among others. Historically, pests have been loosely defined anything that negatively impacts a food producer’s efforts or interferes with crop or animal production.

While we tend to think of pesticides in a modern sense (over the past couple of generations or so), the reality is that pesticides, which are also called “crop protection,” have a very long history of effective use in agrarian societies. Even before the Romans were suppressing weeds with salt in the early years of the first millennium, the ancient Sumerians were controlling insects with burnt sulfur in the 2500 BCE period. Questions facing folks in modern discussions typically revolve around how much of what type is acceptable and to whom.

With so much information and misinformation swirling around the internet — and with so many people not knowing about many resources available on the topic, such as extension agents — we’re going to elevate the conversation a bit. Here are 5 things you may not know about pesticides — from their long backstory to their development and testing to the broad range that is available today.

1. What is a pesticide?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers the official definition for federal purposes: “A pesticide is any substance or mixture of substances intended for: Preventing, destroying, repelling or mitigating any pest; Use as a plant regulator, defoliant, or desiccant; use as a nitrogen stabilizer.”

They can have residential, gardening, or agricultural applications.

All pesticide products contain both active and inert ingredients. An active ingredient prevents, destroys, repels, or mitigates a pest, or is a plant regulator, defoliant, desiccant, or nitrogen stabilizer. All other ingredients are considered inert by federal law, and they are important when considering performance, usability, and environmental acceptability.

The EPA classifies active ingredients as either, conventional, antimicrobial, or biopesticides. Conventional ingredients are those other than biological pesticides and antimicrobial. Antimicrobial ingredients are those that destroy or suppress microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, or fungi. Biopesticides are ingredients derived from natural materials and often have a lower toxicity level than their counterparts but require greater amounts of product to be applied.

Inert ingredients are not necessarily non-toxic. These ingredients act as solvents and improve application by preventing caking or foaming. They also serve as shelf-lifer extenders and protect the pesticide itself from degradation.

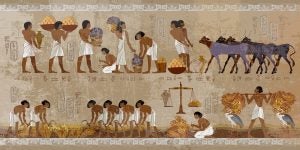

2. A brief history of pesticides

The first use of pesticides on record would be the Sumerian peoples of modern Iraq. Around 2500 BCE the Sumerians used sulfur compounds to repel and kill insects. About the same time, Egyptian and Chinese farmers were combining herbs and oils to the same effect. By 300 BCE, the Chinese were planting crops at specific times meant to avoid pests, while using introducing natural enemies of pests to repel them, such as training ants to attack bugs on citrus. By 1101 CE, the Chinese discovered the use of a soap as a potential pesticide.

By the 1600s, farmers were using tobacco infusions to weaponize the nicotine as a pest repellant, with other herbs and arsenic coming into vogue. Arsenic would be a key ingredient for the next few centuries. By the late 1930s, synthetic pesticides were being developed from petroleum, coal tar, and other inorganic compounds.

3. Volume and usage statistics

Today, global pesticide usage tops 1 billion pounds. The U.S. Department of Agriculture chemical use survey for 2020 soybeans, for example, documents that for that year’s crop, 98 percent of U.S. planted soybean acres received herbicide application, with only 22 percent receiving fungicides, 20 percent insecticides, and 2 percent categorized as “Other.” The top herbicides applied to soybeans in 2020 included glyphosate potassium salt, with 40 percent of acres covered using 50.2 million pounds. Glyphosate isopropylamine salt covered 38 percent of acres using 32.6 million pounds. Sulfentrazone was used on 21 percent of the acres using 3.4 million pounds.

The EPA performs tracking reports of pesticide usage, but those reports typically contain several years at a time. The most recent report covers 2008-2012 estimates.

World pesticide expenditures at the producer level totaled $56 billion in 2012. Between 2008 and 2012, expenditures on herbicides accounted for approximately 45 percent. The U.S. pesticide expenditures at the producer level totaled $9 billion in 2012. In that same year, the U.S. market utilized 678 million pounds of herbicides, 64 million pounds of insecticides, 105 million pounds of fungicides, and 435 million pounds of fumigants.

Per the EPA, between 1990 and 1991, the U.S. pesticide user expenditures totaled $8.3 billion, representing one-third of the world market. Interestingly enough, in those years, the pesticide usage involved 20,000 different pesticide products registered under the Federal Pesticide Law. The total U.S. pesticide usage in 1991 was about 2.2 billion pounds.

One of the reasons for the reduction in gross poundage over the years is because some crops, such as Bt corn, are genetically engineered to produce an insecticidal protein like the one naturally produced by the bacteria species Bacillus thuringiensisis. This has helped to eliminate the need for spraying that particular insecticide. Additionally, the use of some herbicides have coincided with the adoption of no-till practices, thus helping save billions of tons of topsoil by reducing erosion. Tillage had been the primary strategy to control weeds outside of herbicide applications.

4. How dangerous are pesticides?

Keep in mind that all pesticides are designed to kill some kind of living organism, and to that extent, all pesticides must be handled with care. The EPA is among the leading regulators of these products and tests them prior to their release to the public. In evaluating a proposed pesticide for approval, the agency assesses a variety of potential human health and environmental effects associated with it. Potential registrants answer questions in terms of the ingredients’ identity, composition, potential adverse effects, and environmental fate. Pesticides are regulated under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act.

» Related: Top 3 myths about pesticides in your food

It’s estimated that bringing a brand new pesticide active ingredient into the U.S. marketplace costs about $180 million over eight to 10 years, most of which is spent on research. One of the chief considerations taken during this research and development period is any potential dangers from the product. So U.S. consumers can put faith in the fact that the products, while lethal to some living substances at their allotted doses, have been tested for appropriate usage and their safety to humans. Organic and home-made alternatives might not go through as many hoops in terms of testing, but again, consumers should always do their homework when using these products, as they are designed for the purpose of eliminating pests, and if used improperly, can cause damage to people and pets.

5. Organic alternatives approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Whether for large-scale farming or homes and gardens, the USDA maintains a National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances as part of its certified organic program. As AGDAILY.com has reported previously, this list of organic pesticides is updated regularly by the federal government as part of an ongoing decision process shared by the USDA’s National Organic Program, with growers, handlers, environmentalists, scientists, and consumer activists involved.

Chief among this program’s goals is that of health for both the consumer and the environment. While the partners strive for a synthetic-free list, there are some synthetics that do meet approval for the USDA National Organic Program. For a complete and up-to-date list, check out the federal site here.

It’s critical for consumers to keep in mind that just because organic or natural substances aren’t synthetic doesn’t mean they’re not lethal if used incorrectly. The point of the pesticide is, after all, the reduction of pests.

More to learn

The use of pesticides and chemicals in farming is an ongoing topic of heated discussion, with plenty of lobbyist money on all sides. As with most things, the truth is in the tangle. Active producers will quickly tell you that without products such as Roundup, production strategies such as direct-seed, or no-till, farming would be nearly impossible. This is a process where seeds are planted directly into the soil without the process of breaking up the ground with plowing. The benefits to this in terms of soil health beneath the surface are numerous. In addition to prevention of erosion, billions of microbes remain at work beneath the soil, safe from the harsher environment. This essentially creates a permanent cover crop.

The downside of course is, as most have read, that the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and others have named glyphosate, an active ingredient in Roundup, as a “probable” carcinogen, and that had sparked about 125,000 lawsuits by individuals who claim it has caused their non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The IARC’s definition of a “probable” carcinogen includes working the night shift, working as a hairdresser, and eating barbecued meat. The IARC’s conclusions contradict safety reviews by government environmental agencies in Europe, the Americas, and Australia, and no scientific evidence has been brought forth to substantiate the lawsuit’s claims.

So long as there is agriculture and residential-scale food production, producers will be battling pests. Today’s safety standards and measures are in place thanks to the past work of researchers and advocates seeking better products and services. Folks planning to use these chemicals should always act responsibly, keep safety in mind, and follow directions from the supplier. But as a rule, it’s important to remember that without some form of pesticide, commercial agriculture as we know it would simply be impossible. With the world’s population nearing 8 billion, salting the Earth like the Romans just isn’t an option.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana. You can see more of his work at http://www.boycegroupinc.com/.