I may not have grown up on a farm, but agriculture is part of my family tree. My dad was a farm boy in Blackwell, Oklahoma, who wore the blue corduroy jacket of the FFA and paid for part of his freshman year of college by selling three Charolais cows. The farm in Blackwell was bought by my second great-grandpa who came to the United States with his younger brother from Denmark. He later purchased the 160 acres in 1907 from someone who acquired it in one of Oklahoma’s land runs in 1904. I remember looking at pictures of the farm, my grandpa pointing to the barn in one and saying his uncles slept in the loft when the house became too crowded.

Farming is a well-known chapter in my family, and today it is my cousin who owns the family farm. In learning about my family’s farming roots, I discovered another great-great-grandfather who bought property in Virginia where he cultivated the land and his family. That farm was Shadwell.

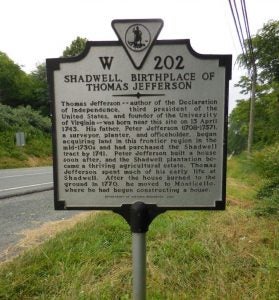

This part of my family’s history had always been a mystery to me. Years ago, my dad sent me a picture of the historic placard at Shadwell that signifies the birthplace of Thomas Jefferson. “That’s where your Grandpa George was born.” Dad told me that this common birthplace wasn’t the same area or property, but the same foundation. Over the years, I gathered a few pieces of information from Grandpa George. He spoke of the bricks from the original Jefferson house that graced his Aunt Mary’s fireplace in Charlottesville. Then there was the issue of Time magazine from the 1940s he passed on to me featuring the restorations at Monticello and including a picture of Grandpa’s uncle in a wagon at Shadwell.

As the pieces came together, the significance of the story unfolded for me. Thomas Jefferson, our third president and writer of the Declaration of Independence, was born and grew up on this farm in the Virginia Piedmont. His father settled there and named it after the parish in London where his wife was christened. The original house burnt down when Thomas was a teenager, leaving only a foundation behind. Later, Jefferson would build his famous residence at the adjoining Monticello. In the years after his death, the Jefferson properties fell into disrepair with some sold or mortgaged. Ultimately, they found their way into the safe hands of those preserving the Jeffersonian estates and history by the 1940s.

It was my second great-grandfather, Downing L. Smith, who purchased Shadwell. The original Jefferson house was gone, so he built his own, and according to family legend, on the same foundation as the original Jefferson house. I like to think Downing knew the significance of the property, becoming one of the many caretakers of 365 acres that one of our founding fathers lived, worked, and was inspired by. Jefferson, in particular, was fascinated with agriculture, always observing, chronicling, and trying out farming practices and bringing in exotic crops to Monticello, Shadwell, Lego, Tufton, and Pantops.

What struck me in learning more about the Shadwell story was the conservation practices Jefferson studied and practiced. Being a prolific writer, Jefferson’s letters spread around and helped usher in different methods in farming. In the book, “Thomas Jefferson, Soil Conservationist,” you see a detailed view of these different techniques:

- Cover Crops — Red clover was a crop Jefferson used to cover the ground rather than allowing the soil to remain bare, which helped the land to revitalize after planting wheat and corn.

- Crop Rotation — Jefferson outlined a seven-year rotation of various types of crops for food and to rest the land, along with grazing sheep to help fertilize the ground.

- Contour Rows — Instead of plowing rows up and down the hill, contouring wrapped around the elevated areas, which prevented the soil from washing away during heavy rains.

- Deep Plowing — At that time, the homemade implements in use limited plowing to a shallow depth. Jefferson created a moldboard which penetrated to a six-inch depth. Other farmers easily replicated and adapted this for their own use.

- Controlled Woodland Cutting — Much of the land was cleared of trees for farming, which led to erosion. Jefferson preserved stands of trees, especially in graded areas.

In 1940, the Thomas Jefferson Soil Conservation District began for Albemarle County. It seemed the Smith family took advantage of Jefferson’s practices, which led to increasing the fertility of the land and quelling the erosion taking place. When our nation was at war in the 1940s, this conservation enabled the farm to make its contribution to feeding the troops and nation when resources were tight.

In 1945, the Smith family sold Shadwell to The Jefferson Birthplace Memorial Park Commission. Today you can’t access the farm, but a plaque along a highway marks its location. To the nation, Shadwell was where one of our founding fathers was born, but beyond that marker on the highway is an incredible story of preservation of two of our nation’s most valuable resources: its history and its land.

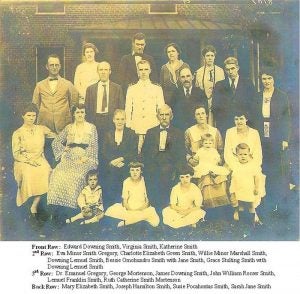

Shadwell not only tells the story of farming and crops cultivated within its borders, but also of the people. Downing L. Smith wrote a chapter of the Smith family history there. His children, five daughters and four sons, shared a mutual birthplace with Jefferson. One was a doctor in Pocahontas County who my grandpa told me had no name, only initials (his name was John William Rosser Smith, or called Ross). James went to the U.S. Naval Academy and was the commander of a naval destroyer. Lemuel became a Virginia Supreme Court Justice. Then there was my great-grandmother Ruth, who left Virginia to teach at a reservation in Arizona. It was at Fort Bayard she married one of the sons of the Danish immigrant who bought the 160-acre farm in Blackwell. But the person who ties the two farms together, born on one and farming the other, was my Grandpa George. In my heart he stands alongside the great men and women that began their life at the historic acreage.

Each of us can look at our family tree and find traces of agriculture because our nation’s history is built and made great by a rich heritage of farming. In a letter, Jefferson wrote, “Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country and wedded to its liberty and interests by the most lasting bands.”

With all the talk of sustainability and the axiom of doing things that are sustainable for not one, but seven generations, discovering what my second great-grandpa did makes me proud of his stewardship. Whether realized or not, the Smiths’ care of the land preserved the Davidson clay loam at Shadwell and, in the end, preserved one of the farms that wrote a chapter not only in my family, but in our nation’s history.

In memory of George Mortensen, farmer, mechanic, and grandpa.

A special thanks to Peter Hatch for advice and assistance with the Jeffersonian history, and John Mortensen for helping with the family history and documents.

Amber Parrow is the marketing director for Fresh Avenue, a group that represents produce farms and producers with national sales and marketing. You’ll find her with a camera in a romaine field or behind the computer promoting brands that promote quality, safe, and nutritious food.