Activists love to use misconceptions about two artificial sweeteners, saccharin and aspartame, to beat Monsanto over the head, unfairly in my opinion. They love to disparage these sweeteners and declare that “Monsanto is the company that gave us saccharin, aspartame, and PCBs.” That’s only partly correct.

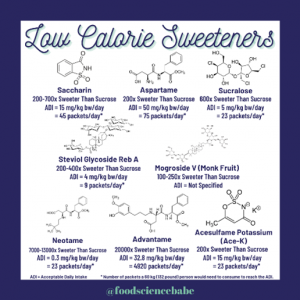

Saccharin (Sweet & Low, Necta Sweet) is the oldest of the artificial sweeteners, discovered serendipitously by Constantin Fahlberg of John Hopkins University in 1879. One evening after working with coal tar derivatives, he failed to wash his hands before picking up a slice of bread. The bread was very sweet, and Fahlberg concluded something he had been working with was the source. Instead of becoming alarmed that he may have poisoned himself, he went back to the lab and tasted everything he had been working with until he found the source.

He obtained patents, and in 1886 found a manufacturer and soon became very wealthy.

Monsanto didn’t give us saccharin, but saccharin did give us Monsanto. In 1901 John Francis Queeny founded Monsanto Co. in St. Louis, Missouri, to manufacture saccharin. Within a few years he added other food additives, such as vanillin and caffeine. In the 1920s, the company expanded into industrial chemicals, which eventually included the very useful PCB compounds, some of which were ultimately deemed very environmentally hazardous.

Early on, saccharin was considered unsafe by some intellectuals. In 1907, then-President Teddy Roosevelt’s director of the bureau of chemistry for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Harvey Wiley, insisted on banning it as “injurious to health.” But Roosevelt was a user, and called Wiley “an idiot.”

It was the end of Wiley’s career, but not the end of controversy over saccharin’s safety. In 1977, the FDA made another attempt to ban saccharin after studies showed it caused bladder cancer in rats. But it was the only reasonable non-caloric substitute for sugar on the market, and opposition from diabetics and dieters caused Congress to override the FDA. So it remained on the market because of an act of Congress. If only we in agriculture could wield such power. Not until 2010 was saccharin finally exonerated, as decades of studies proved to the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency that “saccharin is no longer considered a potential hazard to human health.”

Aspartame (Equal, previous iterations of NutraSweet) wasn’t invented by Monsanto, as anti-Monsanto activists suggest. A chemist assessing anti-ulcer drug candidates for G.D. Searle & Co. in 1965 licked his contaminated finger to lift a page of paper and discovered aspartame’s very sweet taste, about 200 times sweeter than sucrose. After years of rigorous safety testing, the FDA approved aspartame for use in carbonated beverages (1983), and Searle began marketing it for that use and others. In 1985, Monsanto bought G. D. Searle, and spun off the aspartame business as a separate subsidiary, NutraSweet. The subsidiary became a good money-maker for Monsanto, while also attracting anti-Monsanto activists who homed in on the effect it could have on phenylketonurics, people with a rare inherited diet problem.

Aspartame is a peptide (protein fragment) made of two amino acids — phenylalanine and aspartate — held together by a bond provided by a small amount of methanol. Both of these amino acids are required by the human body. Human cells can make aspartate, but phenylalanine must be obtained from the foods we eat.

But for one person in 15,000, worldwide, too much phenylalanine is poisonous. Phenylketonurics lack a liver enzyme that converts excess phenylalanine in the blood to another necessary amino acid, tyrosine. In normal people, excess tyrosine is then eliminated in the stool. People who suffer from phenylketonuria must monitor their intake of foods high in phenylalanine because a buildup in the blood can damage the brain.

Activists also attack aspartame because of the methanol bond. But small amounts of methanol enter our bodies every day in the fruits and vegetables we eat — especially in juices. One orange contains as much methanol as 600 cans of aspartame-sweetened diet soda. But activists can’t kick around Monsanto for aspartame any more: In 2000, Monsanto sold NutraSweet to J. W. Childs Equity Partners.

Sucralose (Splenda) is made from sugar so it’s safe. Right? To make sucralose, sucrose molecules (table sugar) are stripped of three of their eight hydroxyl (OH) groups, and these are replaced with three chlorine atoms. Sucralose is a chlorinated sugar. It might be safe, but it’s not a nutrient anymore, and it must be dealt with by the intestinal tract. Most of it passes through our bodies unchanged, but about 20 percent is absorbed by the blood and eventually removed by the kidneys. Four to seven percent is thought to accumulate in fat or organ tissue.

The other major non-caloric sweetener, Stevia, is a natural sweetener derived from the plant Stevia rebaudiana, native to Brazil and Paraguay. The plant has been used by some native peoples of South America for 1,500 years, and the leaves have been traditionally used to sweeten teas and medicines in Brazil and Paraguay. But only in recent years has it become mainstream in industrialized nations, probably due to the popular preference for things “natural.” Anecdotally, it is known to cause some undesirable intestinal effects (as does sucralose), and it has never been put through rigorous animal testing by government agencies. It instead has been granted GRAS (generally recognized as safe) status by the FDA when highly purified into its constituent glycosides.

My first choice for an artificial sweetener is aspartame, as it is the only one that is an actual nutrient. The amino acids that compose aspartame are usable by our bodies, and if in excess they will be safely excreted.

Jack DeWitt is a farmer-agronomist with farming experience that spans the decades since the end of horse farming to the age of GPS and precision farming. He recounts all and predicts how we can have a future world with abundant food in his book “World Food Unlimited.” A version of this article was republished from Agri-Times Northwest with permission.