“Ow, my bones are so brittle. But I always drink plenty of … malk?!” — Bart Simpson

After Bart glances at the carton, he sees “now with vitamin R!” loudly emblazoned on the side. Of course, there’s no such thing as vitamin R (or malk). And in my view, there’s no such thing as a true milk alternative, only hollow approximations.

It’s said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. But what makes milk … well … “milk”? Does it have to come from the teats of a dairy cow, goat, or other mammal?

With plant-based alternatives on the rise — that all take license with the term in their marketing — is there an authenticity test to make that call?

Do alternatives shamelessly “milk it” by piggybacking on an established brand to make a dishonest buck? Bad pun aside, should government get involved to prevent potential miscommunication/misrepresentation to consumers?

We’ve seen the “Got Milk?” (that popularized the milk mustache) and “Milk Does a Body Good” ad campaigns. It’s unquestionably been engrained into our culture.

But culture is fluid. In an environment where the dairy industry is contracting (for various reasons, including overly aggressive and unwarranted expansion in the past — especially for such a cyclical industry), consumer preference dictates up and comers.

Yet the industry is constantly under fire for a laundry list of unjustified reasons:

Antibiotics: Dairy coops, etc. have a zero tolerance for residuals. A batch is dumped if there’s any hint of antibiotics found. If an animal is sick, by all means treat it. Then it’s industry practice to take the animal out of the herd for a withdrawal period. Basically, purge whatever’s left in the cow’s system until there’s no detectable quantity left. No sane (e.g. profit-motivated) farmer would risk losing their livelihood (and reputation).

Welfare: Modern dairy operations are comparative 5 star hotels, with climate controlled environments, bedding, and room service. Heck, with automated (robotic) milking, cows decide when they want to be milked. Comfort is key. Why? Stress depresses productivity. If a dairy cow is your factory, what’s the point of keeping them flustered?

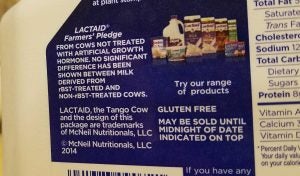

rBST: A biotech derived hormone solution to bolster production. Made by genetically engineered bacteria, it’s a ringer for what’s already naturally produced by cows. It makes their bodies able to more efficiently process feed into milk. I always got a kick out of the label: “No significant difference has been shown between milk derived from rbST-treated and non-rbST-treated cows.” Despite this, Frankenfood fervor got a foothold. There was also the hormone boogeyman to contend with. rBST is a hormone, but a stimulatory one in cows, not people. There’s no “extra” residual in the milk!

Health: Despite assertions to the contrary (by decidedly non-scientific folks) there’s no evidence that milk is a risk factor for [insert ailment here].

Unnaturalness: I frequently hear that’s it’s unnatural for humans to drink cow (or other animal’s) milk. My reply is best summed up by a meme I’ve seen circulating. Basically: “Well Karen [a caricature of a typical (vocal) naysayer], no other animal drinks spirulina smoothies either!”

With these factors in mind — and appreciating how hysterics can take priority over reason — enter plant-based substitutes. This includes rice, soy, and almond milk, among others.

Consider it a media-fueled “de-milking” binge. Despite all the efforts to disassociate from the supposed “evils” of the dairy industry, you have to appreciate the irony in 1) the extraordinary lengths clones will go to (try) and approximate it, while 2) still keeping its namesake!

To be fair, these substitutes don’t taste bad. But they’re not exactly authentic recreations either. They’re watery and lack comparative richness. I always take a warmed shot of milk to coat my throat before karaoke — so I can belt out a rendition of Cher’s “If I Could Turn Back Time.” A substitute isn’t going to put me at peak performance.

Many plants produce exudates (fluids that leak out when cut), but even then we don’t call it “milk” — we call it sap or latex. The “M” word is not only a stretch, it’s an overreach that needs to be reined in.

So that brings us 360 degrees to the original question. Should old-timey, animal-based milk have exclusive use rights to the name?

In the U.S. (at least) it’s almost like milk has been in the public domain. Anyone can brand their product with reckless abandon. But the milk purists have been pushing back to protect their brand integrity.

It’s been argued that soy “milk” has been called such (at least informally) for two thousand years. This tradition, by right, legitimizes use of the name. Then again, this is an isolated case, an outlier in the marketing wars.

What criteria do we use to say yea/nay? Composition? Origin? Merriam-Webster’s dictionary? Milk’s recipe and origin is undeniably animal-centric.

Look to precedent. One can’t call a product champagne unless it actually originates from that region in France. Even U.S.-produced Bourbon has a set of rules tied to the brand. And though they might be co-located in the grocery aisle, margarine isn’t butter. Tofu doesn’t have delusions of actually being meat — though there has been some lawyering up over whether or not certain plant-based products can be called burger, hot dog, etc.

In the EU, there are strict rules for what can be deemed and packaged as milk — and it only includes the conventional kind! Facsimiles are instead called “drink” and the like.

That momentum has hopped the Atlantic, with a number of bills proposed in state legislatures to formally define milk. One passed a couple of years ago in North Carolina, while another just passed both chambers in my adopted home state of Virginia.

Apparently modeled off of the North Carolina bill — I had to take a look. Interestingly, it includes legal protections for not only cow, goat, and sheep milk, but also the deer and horse families (yuck?). After doing a double take (and researching further), there is a growing market for the latter two. Not exactly my cup of yea, but your mileage may vary.

One thing I noticed — and this perfectly exemplifies the disconnect between science and policymaking — is a language lapse. And it’s a pretty glaring one. Equids (horses and donkeys) were mistakenly lumped together with bovines (cows, sheep, goats) and cervids (deer and elk, etc.).

Evolutionary biologists will have a fit! If you’re going to utilize sciency verbiage in a bill — and have it pass both houses without being flagged (at all) for terminological lapses — maybe it’s time to bring some fact checkers into the fray. I call on scientists everywhere to step up.

But I digress. Even though I’m an avowed plant person in training and upbringing, I can appreciate the imperative to insulate the milk brand from further dilution (another bad pun). Milk is milk — but only if it’s animal based. You can accept a substitute, as long as it doesn’t masquerade as the genuine article.

Tim Durham’s family operates Deer Run Farm — a truck (vegetable) farm on Long Island, New York. As a columnist and agvocate, he counters heated rhetoric with sensible facts. Tim has a degree in plant medicine and is an Associate Professor at Ferrum College in Virginia.