In livestock production, “CAFO” stands for concentrated animal feeding operation, and although I grew up on a large dairy (yeah, a CAFO!) I hadn’t heard the term CAFO until I read Michael Pollan’s book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

CAFOs have a bad reputation in mainstream media, but most people don’t actually understand what a CAFO is or what farmers have to do when their operation is considered to be a CAFO. So if you have ever wondered what a CAFO is, or if you haven’t heard of an NPDES or a CNMP, we will delve into what CAFO actually means and why it has long been a key part of the agricultural industry.

How do you define a CAFO?

To define what farm is a CAFO and what farm isn’t, you have to start with the AFO. An AFO is an animal feeding operation, and to be considered an AFO a farm must have any number of agricultural animals that are tended to and fed in a confined space (defined as a place without growing vegetation) for 45 days or more throughout the year. Although farms considered to be AFOs have guidelines to follow like not spreading manure close to bodies of water and wells, it is the farmers considered to be running a CAFO that are subject to inspections and a greater number of regulations.

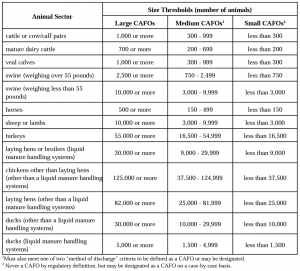

Farms that are considered a CAFO, which was first formally defined by the federal government in 1976, can be designated as small, medium, or large. A large CAFO is considered to be any AFO with more than 1,000 animal units — with an “animal unit” defined as 1,000 pounds of live weight. So, if you have a million or more pounds worth of livestock you’re a large CAFO. That explains why a dairy farm needs only 700 cows to be considered a CAFO, but a turkey farmer needs 55,000 birds! Classifying by weight is considered the easiest way to standardize the system, especially because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t necessarily care how many animals you have, it’s how much manure there is, since manure is the potential pollutant.

Here is the breakdown from the EPA based on various animal types and operation sizes:

North Carolina, Iowa, Wisconsin, and California are among the states with the largest numbers of CAFOs, and EPA data show the total number of CAFOs across the U.S. as topping 20,000.

CAFO isn’t a code word for a big bad factory farm — it is simply a sizing guideline created by the EPA. You can think about it just like you think of high school sports: For example, did you play soccer or football in class A? That means you went to a school with a larger enrollment than someone who played soccer in class D. But just as we never look at class A as being worse than class D, we shouldn’t consider CAFOs to be something worse than their non-CAFO counterparts.

Across the United States, 98 percent of all farms are family owned, and those family-owned farms make up 88 percent of production — whether they’re CAFOs or not. The primary reason CAFOs have grown in number is because instead of supporting one family unit, farms now support multiple generations of the same family.

When did ‘CAFO’ start being used?

In 1972, congress passed the Clean Water Act, in which AFOs were identified as potential sources of pollution to water sources. Through this law, the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) was created to regulate effluent from CAFOs, and the NPDES is run and regulated by the EPA.

It was in that act, under a section for general definitions, that the term “concentrated animal feeding operation” was used. The act said:

“The term ‘point source’ means any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance, including but not limited to any pipe, ditch, channel, tunnel, conduit, well, discrete fissure, container, rolling stock, concentrated animal feeding operation, or vessel or other floating craft, from which pollutants are or may be discharged.”

The first specific definition of CAFO was created by the EPA in 1976 and remained in effect for more than 25 years. Yet increases and changes to farm size and production methods required an update to the permit system, so the regulations guiding CAFO permits and operations were revised in 2003.

The NPDES has to regulate other sources that could contribute to water pollution too, like municipal waste water treatment facilities, stormwater discharges, and industrial waste.

The history of NPDES and CAFO begin with the Cuyahoga River in Ohio. In 1936, the Cuyahoga caught on fire, fueled by the trash and oil on the surface from the local factories and cities. This river caught fire multiple times, but in 1969 there was press coverage for the first time. Then in 1970 the United States celebrated its first Earth Day, which prompted thousands of people to march down the Cuyahoga.

The responses to the river fires pushed Congress to pass the Clean Water Act, which aims to stop much of society’s pollution from making it to waterways.

So do CAFO regulations only control pollution of water?

The NPDES only deals with the pollution of water, but agriculture, likely other vital industries in the U.S., has the potential to expel pollution into the water, soil, and air. To avoid pollution of any kind, and help farmers to reduce their global greenhouse gas impact, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has guidance in place.

The USDA has a program that farms take part in voluntarily called the comprehensive nutrient management plan (CNMP). A CNMP is a plan that combines the management and capabilities of the farm with the specific manure and wastewater output that the farm will have based on their operation. It is a plan that is custom to the operation, and it assures that the farm will comply with the NPDES’s rules, but also better utilize the “waste” nutrients on the farm. Michigan State University has a great article that breaks down the components of a CNMP.

So, what’s the verdict on CAFOs?

Critics of CAFOs point to the close proximity of animals being a potential source of the spread of pathogens and the release of methane, as well as impacting the quality of the animal’s life. There have also been concerns raised over the general nature of consolidation in agricultural operations and the reliance on corporate contracts.

However, food security is a major benefit of these types of operations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that CAFOs “can provide a low-cost source of meat, milk, and eggs, due to efficient feeding and housing of animals, increased facility size, and animal specialization.” CAFOs are also known to improve local economies and increase employment opportunities. And as animal housing has been modernized with climate controlled systems and advanced health and welfare monitoring, as well as limited amount of land being available for agriculture in the U.S., many see CAFOs as a valuable path forward in animal production and care.

CAFO is a term meant to define the size of a farm, and those that are considered a CAFO have to prove to the government that they are not polluting waterways. So CAFOs are actually just farms that are farming sustainably and proving it through a rigorous inspection and documentation process.

» Related: Senate bill aims to eliminate all CAFOs in 20 years

So when Sen. Corey Booker and his allies try to eliminate CAFOs, he’s trying to eliminate a huge system that helps farms keep pollution out of water, is an important piece of food security for Americans, and provides support in events of an accident or storm.

Elizabeth Maslyn is a born and raised dairy farmer from Upstate New York. Her passion for agriculture has driven her to share the stories of farmers with all consumers, and promote agriculture in everything she does. She works hard to increase food literacy in her community, and wants to share the stories of her local farmers.