U.S. farm policy has spent much of the past three years responding to two major economic shocks: the U.S.-China trade war and the coronavirus pandemic. Both events had negative impacts on U.S. agriculture. The trade conflict led to lost export sales of some commodities, especially those like soybeans that relied on sales to China. The coronavirus pandemic disrupted many agricultural supply chains, especially for produce, meat, and dairy products.

A series of “ad hoc” farm programs attempted to quantify the specific economic harm these events caused for U.S. farmers and ranchers and provide compensation in the form of direct payments. These programs were ad hoc in definitional sense of the term; they were quickly designed as a solution to a specific problem. This stands in contrast to traditional farm programs provided through the Farm Bill legislative process that maintain a consistent design across multiple years in an attempt to provide a safety net in the event of unpredictable negative future events.

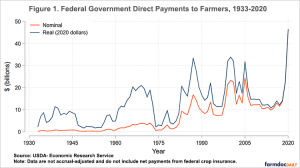

The result of these ad hoc programs was the highest level of direct farm payments in US history (see Figure 1). Direct farm payments in calendar year 2020 are estimated to be approximately $46 billion, higher in both nominal and real terms than any year recorded, including previous peaks during the 1980s farm crisis and the period of low commodity prices from 1998 to 2005. Approximately 80 percent of 2020 payments come from ad hoc programs. However, total farm payments in 2020 did not reach record levels when considered as a proportion of net farm income because prices for many commodities have shown surprising strength, especially since the summer of 2020.

Recent ad hoc farm programs include the Market Facilitation Program (MFP), which made two rounds of payments between 2018 and 2020 to compensate farmers for lost exports due to the trade war. The Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) in 2020 addressed commodity price declines related to the ongoing pandemic. Other ad hoc programs provided compensation for losses related to specific natural disasters or were non-farm programs available to all small businesses as part of broad coronavirus-related government relief.

The distribution of these ad hoc payments changed over time, becoming more diffuse across commodities and regions. Producers of row crops (mainly corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton) received 94 percent of MFP payments. Specialty crop, livestock, and dairy producers were a much larger part of the more recent CFAP program, so that row crops received 39 percent of CFAP dollars. As ad hoc payment dollars were spread across more and more commodities, payments also became more widely diffused across states and regions. Where MFP dollars targeted major production areas for just a handful of crops, CFAP dollars reached all parts of the country. This is especially true if you consider payments per cropland acre.

The prevalence of ad hoc payments since 2018 suggests that the existing farm safety net provided in past Farm Bills had real or perceived inadequacies in the context of the economic harm caused by the trade conflict and the pandemic. Existing programs would not quickly provide sufficient support to the sectors of the farm economy.

Experience with ad hoc payments may inform future farm policy. Ad hoc programs like MFP and CFAP attempted to provide greater support to farmers in a more timely and targeted manner than is the case with farm bill programs. Simultaneously achieving these objectives was difficult. Attempting to provide ad hoc payments before the end of a production cycle (as is common with many farm bill programs) required USDA to predict the magnitude of the economic harm caused by the trade war and the pandemic for specific commodities at specific points in time. Some prediction error in this process is inevitable.

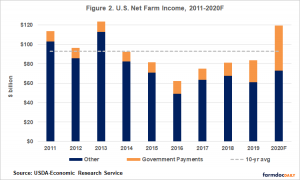

For example, the second round of CFAP payments were based on the decline between January and July 2020 of the expected harvest-time price for the 2020 crop. For some commodities like corn and soybeans, these expected price decreases were later erased by the market rally that began in August. For these commodities, economic harm from the pandemic may have been more than offset by other market dynamics. In fact, USDA’s most recent forecast puts 2020 net farm income at $120 billion, second only to the record farm income of $124 billion in 2013 and well above the 10-year average of $93 billion (see Figure 2). This has led some to question the necessity of these ad hoc programs.

Some ad hoc support for farmers related to broader pandemic-related government aid is likely in 2021, but ad hoc programs of the size and scope seen in 2020 are unlikely to continue into the future. These programs are expensive and difficult to design in a manner that achieves all of the objectives inherent in US farm policy. As a new administration takes the reins at the USDA in January 2021, it is likely to impose additional budget discipline on farm spending. The incoming administration is also likely to place greater priority on environmental conservation, so future farm policy will have additional objectives to meet. The rationale for farm programs, particularly programs designed to boost farm income as were MFP and CFAP, is likely to change as well.

This is a presentation summary from the 2020 virtual Illinois Farm Economics Summit (IFES). A video of the webinar and PowerPoint Slides (PDF) are available here.