“Forget whiz-bang technologies that are supposed to solve climate change. An ancient agricultural practice that removes carbon from the atmosphere is getting fresh attention and game-changing cash from big companies.”

So starts an article on biochar in the May 17, 2023, Wall Street Journal. Biochar is getting a lot of attention these days because it is a high-carbon product that can be applied to soil with reasonable assurance that the carbon therein will be sequestered for a century. The problem? It costs too much. But that may be changing.

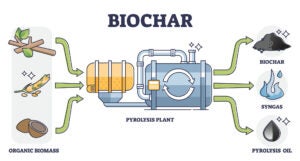

What is biochar and how is it made? Biochar (a kind of charcoal) is made by burning organic materials (plant waste, manure, etc.) at high temperatures with oxygen restricted (pyrolysis). Whereas about 90 percent of the carbon in a waste product would be given back to the atmosphere if allowed to decompose naturally, the high temperature, low oxygen burn converts 50 percent or more of the carbon to a black, solid product very resistant to decomposition. Added to soil, it will hold large amounts of water and nutrients for plant use.

In modern pyrolysis operations, the waste material is completely enclosed and does not actually combust. Heat decomposes the biomass into combustible gases and biochar. The heaviest gases are condensed into bio-oil and the lighter ones become syngas. Both can be burned to heat the process. The burning of these oils and gasses, of course, result in the release of CO2, but much less than if the biomass was left to naturally decompose.

The benefits of adding biochar to soil has been known for centuries. About 7,000 years ago the Aztecs were growing their crops on Terra Preta (black earth) soils they had created by design (or accident). They burned their organic wastes from crops, cooking, and perhaps even human excrement. These wastes were burned in pits, probably covered to hold in smoke and restrict oxygen. The resulting ash and charcoal-biochar was spread on their garden soils, producing, over time, a very productive “black earth.” These black earth plots have been discovered all over the Amazon.

If you look at biochar under a microscope it appears as a chunk of tiny, stacked tubes. It is extremely porous with a surface area of up to 1,000 square meters per gram (0.35 oz.). It will soak up five times its own weight in water. It also has a very high cation exchange capacity (CEC), giving it the ability to bind large amounts of positively charged ions such as ammonia. It comes precharged with phosphorus, potassium and sulfur, because they are preserved with pyrolysis, but nitrogen sources must be added. Once fully charged, biochar resists the leaching of these nutrients. The high CEC makes biochar very valuable for tropical soils that rapidly lose nutrients to rainfall. And for arid farmland, its ability to store water is very valuable.

Feedstock and the pyrolysis temperature affect the parameters of the resulting biochar. Temperatures below 400 degrees centigrade usually result in acidic biochars, while those above 400 degrees result in alkaline biochars. Low temperature pyrolysis results in higher amounts of biochar and less gas. For high amounts of gas and oil, pyrolysis of 1800 degrees is used.

Dr. Stephen Machado, working at the Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center (CBARC), has done extensive research on biochar additions to arid and semi-arid soils. Data from small plots at the center where he applied 5 to 10 tons of Douglas fir biochar cooked at 700 degrees C, wheat yield increases of 12 percent to 33 percent, and pea yield increases of 15 percent to 20 percent were observed. Farmer plots where 2.5 tons were applied did not result in significant increases. Future farmer plots are planned at a five ton rate.

So what about price? Hard to figure out. Most quotes are dollars per cubic yard. And weight per cubic yard can vary widely. Best I can do is estimate $400 to $500 per ton in truckload quantities. When it gets down to $100 per ton it would be within reach for at least some farmers. They wouldn’t have to treat the whole farm in one year.

Some companies are investing in technologies, such as collecting CO2 at the smokestack and pumping it into underground storage, that cost over $600 per ton of CO2 collected. It’s time for companies to invest in biochar production and sell it to farmers at a price they can afford. They could give it away and still cost them less than pumping it into the ground.

One company has sold American Airlines on a new technology that I find a bit silly. Graphyte , a startup company, intends to collect agricultural and forest waste, compress it into shoebox size blocks, seal them with a special barrier (probably plastic) to prevent decomposition (forever?) They are charging American $100 per metric ton of CO2 sequestered. Not environmentally sound in my opinion.

The soil and forests need the carbon and nutrients they plan to sequester forever. Charge the airlines a little more and make it into biochar to sell to farmers at a reasonable price. Help rejuvenate our soils, not lock away important nutrients our soils need. Bill Gates is an investor. Send him a letter.

Jack DeWitt is a farmer-agronomist with farming experience that spans the decades since the end of horse farming to the age of GPS and precision farming. He recounts all and predicts how we can have a future world with abundant food in his book “World Food Unlimited.” A version of this article was republished from Agri-Times Northwest with permission.