Some discoveries are worthy of a little scientific jig.

In a feat for the record books — a groundbreaking revolution if there ever was one — a blind man was given the ability to (crudely) see again, thanks to gene therapy.

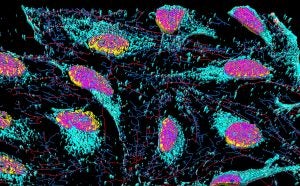

A harmless viral vector was used as a middleman. It delivered a photoreceptor (light sensing) gene from a green algae, specifically targeting the patient’s retinal cells. These allowed them to produce a new protein – one responsive to light intensity. In a sense, a biological pair of corrective lenses.

To be fair, gene therapy alone wasn’t fully restorative — the patient also required special goggles to amplify light signals. And while the patient couldn’t see color or fine detail, he could discern shapes. For the first time in 40 years, he was able to “see” and count objects on a table.

Yet mind-blowing milestones like this might evoke a spectrum of responses: from mind-numbing “meh” to cataclysmic social media rants, all because it’s seen as unnatural.

For sure, it prompts questions about society’s long-held reverence for nature’s divine design. With that little snippet of green algae forever entwined in his DNA, is the patient still human? Is he a bona fide GMO? What’s our tolerance for molecular scale incursions and so-called genetic pollution? Just what is natural, and how does that stoke fears of genetic stranger danger?

Obviously, this case of therapy was medically intentional. But what about seemingly accidental cross-kingdom mixing? To sound Shakespearean: Does intent a GMO make?

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (highly recommended) tells an intriguing story. One of an African-American who succumbed all too early to cervical cancer in 1951. Ordinarily, as a pre-Civil Rights Era minority (and female, a regrettable double indictment at the time), this might be where the story ends, but Henrietta was unique — and terminally ill. A doctor biopsied her cervical cancer cells, and found that they had a superhuman trait: they were biologically immortal. Basically, while cultured cells from other patients would eventually cease dividing and die off, Henrietta’s could divide an infinite number of times. They were literally a genetic composite, with the human papilloma virus taking liberties and inserting its genes into the human genome. Turns out these cells (called HeLa, from Henrietta Lacks’ name) became stapes of biomedical research — used to develop the polio vaccine, among other things. Some have argued HeLa cells are so different from the original source materials that they deserve their own scientific name!

The reality is that nature is a cauldron for opportunistic, interspecies trysts (through no fault of the human host in this case, of course).

Indeed, viral invasions are the rule, not the exception. Our genomes are littered with remnants of past viral incursions — making us all honorary GMOs. Fortunately, they’re generally benign. These are considered horizontal (asexual — kind of like incidental handoff) events, rather than sexual (vertical, like passing genes down from parents to offspring). They must provide some benefit, otherwise it wouldn’t make much sense to maintain that extra genome bloat.

Even parasitic wasps are in on the debauched (a)sexual action. They’ve been found to leave behind some symbiotic viral material after laying eggs (think of the film Alien, chest-burster style), in caterpillar victims. This virus is ordinarily supposed to suppress the immune response of the caterpillar host, so the wasp larvae can grow unchecked. However, the caterpillar has been found to have repurposed and integrated some of this viral DNA in a “bonus” capacity. Turns out these sequences are protective against a totally different virus that’s lethal to the caterpillar, and transmissible vertically to their offspring (for those that survive being parasitized)!

Agriculture has been grappling with the GMO question for 25+ years. Be prepared for the purity prima donnas to strike in the medical field. But in any sector, the appeal to nature trope is a massive continuity error in logic. There is no sacred chastity belt that maintains species integrity.

Like humans, plants (including crops) have similarly benefitted from genetic “loaners” that shaped their evolutionary history.

A study by an international team of scientists has concluded that natural genetic engineering facilitated the movement of plants from water to land. Specifically, genes from soil bacteria were horizontally transferred to algae after mixing and mingling in the same spaces (river beds, puddles, rocks, etc.). These borrowed sequences equipped them with the necessary tools to deal with the unforgiving realities of terrestrial life.

Another study contends that cereal (grass) crops like wheat and barley routinely borrowed genes from grassy neighbors to make them more resilient in the face of stress.

A paper published in 2019 found 15 naturally occurring transgenic (read: GMO) species, specifically sequences from Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a bacterium colloquially known as nature’s genetic engineer. Its by-the-book natural GMO MO (no human intervention necessary) is where we got the inspiration to start genetically modifying plants in the first place.

Similarly, the humble sweet potato has been identified as a naturally occurring GMO due to the presence of decidedly specific Agrobacterium sequences in its genome.

Moreover, even grafting plants together, a time-honored horticultural practice, can prompt a type of asexual intimacy that prompts the seamless exchange of organelles between partners.

So, in deference to nature, just what is the genuine article? Everything, because life is dynamic, not static and immutable. No crop we consume today is remotely like its forerunner. Flexing eugenic purity credentials needlessly typecasts “faux” food for the wrong reasons. Close encounters of the genetic kind are the norm, not the exception.

In light of nature’s infinite (and evidently promiscuous) genetic bounty, does where or how we obtain new genetic materials for crop improvement matter? How about generative method (GMOs or gene editing — with the comparative precision of a surgical scalpel, or conventional breeding — a bludgeon)? How should these be treated by regulators and risk managers? If we abide by the appeal to nature argument, then GMOs should rightfully be mainstreamed without prejudice.

From a marketing standpoint, “just as Mother Nature intended” is an empty platitude to divide and generate fear of the “other.” Much like the firestorm that erupted when hybridization was first attempted, it’s time we had these uneasy negotiations in our heads to address any cognitive short circuits.

Tim Durham’s family operates Deer Run Farm — a truck (vegetable) farm on Long Island, New York. As an agvocate, he counters heated rhetoric with sensible facts. Tim has a degree in plant medicine and is an Associate Professor at Ferrum College in Virginia.