Ranchers who operate along the U.S.-Mexico border have seen an increase in nefarious individuals crossing their land and even showing up at their doorsteps.

When Sue Chilton answered the door of her house on the Chilton Ranch in Arivaca, Arizona, one day in 2022, she immediately recognized that an MS-13 gang member was darkening her doorway.

“She was home alone, and she recognized his tattoos as those of an MS-13 member,” said Jim Chilton, Sue’s husband of 60 years. “There was a woman and three guys, and Sue would only talk to the woman.”

With a master’s in Spanish language and literature and 50 years of teaching experience to back up her bilingual skills, Sue speaks fluent Spanish — a language that’s proved useful when dealing with unannounced visitors at her ranch.

These visitors claimed they wanted to use the phone. Sue refused. Then they said they wanted something to eat.

“So, Sue put together sandwiches and water,” her husband said. “They ate at the picnic bench, and they had a beautiful lunch.”

A few weeks later, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended a group of MS-13 gang members about 200 yards west of the Chiltons’ home.

The U.S. Department of Justice profiles the MS-13 gang on its website. Formed by Salvadoran immigrants, the group is listed as well-organized and heavily involved in criminal enterprises. Members are usually trained in guerilla warfare and the use of military weapons; they are notorious for using violence to achieve their objectives.

As the Chiltons and many other American Southwest families know, the gang has an active presence along the United States-Mexico border.

Border issues present myriad challenges

The American West invokes idyllic scenes of cattle grazing large swaths of rangeland. For ranchers along the border, the land serves as both a home and a workplace, where life revolves around the rhythm of tending to livestock and managing finite resources in mesquite grasslands and deserts while navigating the constant ebb and flow of the border’s impact.

The Chiltons’ ranch covers about 50,000 acres and includes 14 miles of exposure to the border. However, many ranches stretch across hundreds of thousands of acres of rolling hills, with creosote bushes, cactus, and mesquite scattered as far as the eye can see. In many places along the Chiltons’ border fence, the only divider is simple barbed-wire.

The remoteness of the land is difficult to describe to anyone unfamiliar with the vast and rugged nature of the Southwest. In stretches along the border; the solitude is palpable.

For decades, ranching along the border has manifested challenges and complexities where sprawling landscapes intertwine with violence and strife, and the picturesque hills have their own sets of watchful eyes coupled with high-tech equipment and artillery power.

“We have foreigners on our mountains observing everything we do,” Jim Chilton said, describing the mountain ranges surrounding his ranch. He explained how cartel scouts keep a watchful eye with high-tech vision and communication equipment on the trails and the ranches below. “To the south and west, there are three bunkers disguised with camouflage; on the other range, they have ten bunkers.”

On the Mexican side of the border, Chilton said they’ve had gun battles. Meanwhile, north of the fence, it’s sometimes a matter of safety over caring for livestock.

“We’ve been told by Border Patrol and the U.S. Forest Service not to go near the border when cartel factions are battling for control of these largely unpatrolled routes through our ranch,” he said.

The Texas Farm Bureau, along with the American Farm Bureau Federation and 49 other states, wrote a letter to the Homeland Security, Agriculture, and Interior departments pleading for assistance detailing the concerns of the members working along the border.

Farmers and ranchers described how their crops and property are damaged, causing financial hardship, but also the dangers of human smugglers (otherwise known as “Coyotes”), who abandon people, steal vehicles, vandalize property, and threaten both the safety and livelihood of farm and ranch families.

Even the brown and white signs posted in areas that may attract visitors along the border read, “TRAVEL CAUTION: Smuggling and illegal immigration may be encountered in this area.”

“Our cowboys have refused to go down to the border and gather cattle,” Chilton said. “We’re fortunate that the cattle naturally drift back north during the summertime when we open gates.”

While not all undocumented individuals are bad actors, many of them are in desperate situations or have ties to criminal organizations. And having people who choose to do bad things crossing ranchers’ land can present various challenges and concerns, from property damage to livestock disturbances, security risks, environmental impacts, and even legal complications.

“Friends in other states can’t comprehend what it’s like to live on the border and have 3,050 of your ‘closest friends’ walk through your ranch,” he said. “They’re just stunned.”

The border remains a hotspot for drug trafficking, illegal arms trade, human trafficking, and smuggling operations. In federal judicial districts along the U.S. southern border, drug trafficking is one of the most prosecuted crimes, with marijuana trafficking decreasing, while illicit drugs like fentanyl rising 480 percent higher at the border than it was in the past three years.

The Department of Homeland Security even warned recently that terrorists and other criminals may exploit these convenient south-to-north, little-patrolled security gaps, which can be freed up by a strategically planned, cartel-controlled mass migrant diversion.

“It’s a national security issue. A humanitarian issue. And, it’s an environmental issue,” Chilton said. “It’s so outrageous. The idea that they’re bringing drugs through my ranch to poison our people.”

The harsh desert climate takes its toll on border crossers. Ranchers are faced with repairing damaged waterers broken by thirsty travelers or choosing how to handle those travelers who approach their homes looking to use a phone or asking for food or water.

“I’ve had as many as 17 drug packers in my front yard,” said Chilton. “I took my gun, and I slithered out and yelled, ‘Agua agua! Water, water!’ Everybody filled up their water bottles and took a drink, and then I yelled, ‘Adios!’ and they marched on.”

“It’s so outrageous. The idea that they’re bringing drugs through my ranch to poison our people.” — Jim Chilton, Arizona rancher

Over the past decade, Chilton has scattered dozens of drinking fountains across his ranch. The first fountains were installed in 1993. It was at that point that border traffic had increased enough that deaths were occurring more frequently as people crossed the desert in sweltering heat.

Today, there are 29 water fountains with nearly constant water. Even with the fountains, crossing the rugged, mountainous, desert land is still treacherous. Last year, one of the wells in a pasture that Chilton wasn’t using had a solar panel problem, and it quit pumping water. The well wasn’t immediately fixed with a long “to do” list of other repairs waiting on the ranch and because there were no cattle in the pasture.

A woman was subsequently found deceased near that well in October 2023. It was the second death on the ranch that year — something that the Chilton family does not take lightly.

“People don’t need to die,” he said. Despite not planning to turn cows out in that pasture until July 2024, the panels were repaired shortly after the fatality, and that site was able to provide water again.

He also noted that a man passed away in April 2023, about 15 miles inside of the ranch. One of the cowboys was riding and gathering cattle, and Chilton says he was horrified to come across the body.

Other ranchers have simply stopped helping people.

“It’s a tough call, but we feel that it encourages them, and it’s dangerous,” said another Arizona rancher, who spoke to AGDAILY on condition of anonymity.

There are numerous tangible signs that people have been across these ranches, some of which act as heartbreaking reminders of what is happening in this isolated space.

Clothes, backpacks, and other trash items are often left behind as immigrants move through these ranches, leaving the property owners to clean up the mess.

Aside from leaving unsightly trash scarring the landscape, trash is picked up and consumed by cattle and wildlife, who are indiscriminate eaters. Trash blocks the intestines of cattle; they bloat, and then they die.

Dr. Gary Thrasher, a veterinarian who worked with Animal Health and Border Relations, dubbed the death phenomenon “Oxxo poisoning” — many of the necropsies his team performed on dead cattle found plastic bags from Oxxo, a common gas station in Mexico.

“Each year, we lose 1 to 2 percent of our herd after they consume plastic left behind,” Chilton said. “I’ve estimated that over 25,000 tons of trash in the Tucson sector have been dropped. And that’s a very conservative number.”

Still, there are other symbols of the hazards in the region.

While border authorities have refuted allegations of “rape trees,” a term used to describe landmarks where women are sexually assaulted and their undergarments left behind as a calling sign or point of pride, groups such as Amnesty International report that up to 60 percent of illegal, female crossers are assaulted; another report in 2017 shares similar, striking numbers.

Nobody takes up cattle ranching because it’s an easy industry. But, the emotional and financial toll taken by frustrations of life on the border are undeniable. Not only are the regulations, fees, and enforcement of regulations a challenge for managing mixed land ownership (including federally-designed multiple-use ranch land), but costs from vandalism, theft, and daily disruptions of operations add to normal operating expenses for ranchers on the border.

A University of Arizona study completed in 2000 estimated the additional costs that border ranchers face in the wake of illegal immigration. Funded by the Carbon Chair of Agribusiness Economics and Policy, the study indicated that for every 100 pounds of weight that a calf puts on over its life on the ranch, there is an additional $15 in cost to the rancher incurred in areas impacted by illegal immigration.

The border wasn’t always a violent epicenter

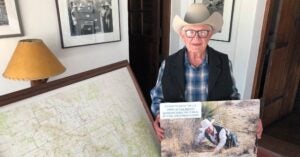

In stark contrast to many of their illegal visitors, Jim Chilton’s ancestors drove cattle to Arizona in 1886. The 84-year-old rancher’s family has raised cattle in Arizona for five generations, purchasing the Chilton Ranch in historic Arivaca in 1987.

“We had no idea when we bought this ranch that there would be an immigration and drug packing issue,” said Chilton.

Looking back on the 1980s and ’90s, local ranchers are aligned in describing people coming across the border looking for a better way of life — humble and ready for work.

Chilton says that both the demographics and the volume of people coming over have changed.

“Border Patrol’s intelligence officer estimates that about 20 percent are packing drugs,” he said, “and the other 80 percent are people who have been kicked out of the country and are trying to get back in. Or criminals wanted either in their home country, or in this one.”

After the recession, Chilton said that the type of border crossers changed dramatically: “That’s when the cartels took over all the trails; they ‘own’ them now.” U.S. Border Patrol data shared by Statistics shows that 2011 marked a sharp increase in the number of apprehensions and expulsions in the region, from about 340,000 that year to more than 2.2 million in 2022.

During the early 2000s, Chilton’s five motion-sensor cameras captured about 230 images yearly. Now, the ranch is capturing from 1,000 to 1,500 images annually of people (mostly men, and very few women), often dressed in camouflage clothing and carpet shoes, a type of footwear made to eliminate tracks through the desert.

“I believe in having evidence,” said Chilton, who has a thumb drive with over 3,050 images. “It’s outrageous.”

He also said he is aware of cartel-paid foreign scouts stationed in the border mountains, including on his ranch, with encryption equipment and satellite and radio technology helping to usher border-crossers through.

Those things add to the fear and danger in a region that has become increasingly tense.

In 2010, a Southern Arizona rancher, Robert Krentz, and his dog were shot to death on their ranch by a border crosser while checking cattle waters. Authorities followed tracks from the shooting site to the border, where the trail was lost.

That same year, Jesús Rosario Favela-Astorga was sentenced in federal court to 50 years in prison for the murder of U.S. Border Patrol Agent Brian Terry on David Lowe’s ranch near Rio Rico, Arizona.

In 2015, a local well driller was kidnapped along the border. Drug runners buried his pickup, held him at gunpoint, kidnapped him, and drove him and his pickup across state lines from New Mexico into Arizona.

Physical borders are varied and sometimes non-existent

The U.S.-Mexico border stretches along 140.4 miles in California, 372.5 miles in Arizona, 179.5 miles in New Mexico, and 1,241 miles in Texas.

The Department of Homeland Security began operations in 2003 in the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and after the passage of the Homeland Security Act. Over the years, the budget allocated to border security has experienced substantial growth. This growth includes funding for additional agents, advancements in surveillance technology such as sensors and cameras, and the construction of physical barriers along parts of the border. In 2023, the fiscal year budget included $17.5 billion and 65,621 positions.

The approach to border security has continually evolved, influenced by changing political landscapes and priorities. It’s a complicated issue mired by changing administrative strategies, but across the board, the impacts of administrative decisions and reform have impacted ranch families.

“Border patrol is made up of a lot of really good guys, and we have a good relationship with them,” Chilton said. “They’ve been helpful in different instances, but at this time, agents are processing people and releasing them into the country. I haven’t seen a border patrol agent checking canyon routes through on my ranch for three months.”

Chilton also noted that a major highway checkpoint between Nogales, Mexico, and Tucson, Arizona, was left unmanned for weeks.

AGDAILY reached out to U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, requesting more information on how the volume and demographic of border crossers has changed and why ranchers such as the Chiltons have not seen officers patrolling the border in recent months. No response was received prior to publication.

Along the border, the fencing is varied. With nearly 1,950 miles of land stretching the U.S.-Mexico border, only about 38 percent is fenced. Former President Donald Trump added 450 miles of barriers along the border between 2017 and 2021, much of it being the bollard-style fencing that was frequently shown on news channels.

While barbed wire keeps cattle in their place, it’s easy to cut and drive through or simply crawl under. In other places, jack fencing consists of a series of steel X’s set perpendicular to the border, with steel cross-beams running through them. Jack fencing slows down vehicle traffic except when ramps or other equipment are used to drive over the top.

In other areas, simple steel posts are driven into the ground. They’re easy to walk by but do act as a deterrent to vehicle traffic.

“It’s our custom, our tradition, and our culture,” Chilton said. “We have a family cemetery on the ranch, so I’ll either be here on top of the ground or below ground.”

Jim and Sue Chilton’s sons, will one day inherit the ranch. As long as the couple manages Chilton Ranch, they’ll live the uneasy balance of continuing their family’s ranching heritage while juggling the challenges of life along the border.

This article is the first in a three-part series delving into the unique hazards for ranchers who operate near the border with Mexico and how they respond to a changing landscape that includes illegal immigration, drug cartels, and human trafficking. The explorative series, titled The Dangerous Divide, is an AGDAILY exclusive.

Heidi Crnkovic, is the Associate Editor for AGDAILY. She is a New Mexico native with deep-seated roots in the Southwest and a passion for all things agriculture.