Editor’s Note: This is the second in a three-part series discussing faith and religious participation in rural America. The explorative series, titled Religion in the Heartland, is an AGDAILY exclusive.

Seismic shifts in membership are being reported in communities of faith across the United States, but this seems quite the overstatement when considering the gross number of self-identified believers compared with church attendees — especially relative to a population growing at a historic rate of speed. The fact is, with 70 percent of Americans identifying as Christian today, at a population of 330 million, there are millions more than in 1990 when 90 percent of a 250-million American nation identified as such. The difference is actually about 231 million to 225 million, if we include the children of those adults identifying as such.

But therein lies the concern. What about the younger generations?

As a study conducted by the Pew Research Center notes, there appears to be a transmission failure between the generations. Just as the Baby Boomers were less inclined to religious identification than their parents in the World War II Generation, their children in Generation X, and their Millennial grandchildren are following that trend toward the term “unaffiliated.” It’s worthy to note though, that “unaffiliated” does not mean atheist or nonbeliever. Rather it means the individual does not identify with a particular denomination, church, or organized religion. Meanwhile, some of the highest participation percentages remain in rural America, with big growth in the independent evangelical community and non-denominational groups like cowboy churches.

Some would point to politics in the pews; others cite the split between supporters of traditional marriage and those backing the LGBTQ+ community. But as a lifelong small-towner myself in rural America, I’ve had too many conversations on this topic to find the answer that simple.

The great withdrawal

Even before the COVID lockdown in 2020, which most experts agree put a giant kibosh on church attendance and group activities, Americans were steadily dropping out of what’s referred to as civil society. So severe has this downward trend been, the United States Congress’ Joint Economic Committee released in 2019 its bipartisan report, The Space Between: Renewing the American Tradition of Civil Society. America, as all fans of history know, was indeed founded by members of small clubs in rural churches, pubs, and trade guilds, all the way back to the Colonial days. Such a distinctly American phenomenon it was, French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville noted it during his trip to the U.S. in 1831 and wrote in his first volume, Democracy in America, that:

“Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but they also have a thousand other kinds: religious, moral, grave, futile, very general, and very particular, immense and very small; Americans use associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they create hospitals, prisons, schools. Finally, if it is a question of bringing to light a truth or developing a sentiment with the support of a great example, they associate. Everywhere that, at the head of a new undertaking, you see the government in France and a great lord in England, count on it that you perceive an association in the United States.”

In the U.S. Constitution, freedom of peaceable assembly is, after all, listed in the First Amendment, right there with freedom of speech, press, and religion. To the founders of the nation, they all went hand in hand. But gone with the wind that seems to be.

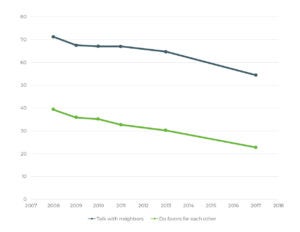

According to the Current Population Survey, between 1974 and 2018, the share of American adults who reported spending an evening with a neighbor several times a month dropped from 44 percent to 29 percent. Between 2008 and 2017, the share of adults who reported talking with neighbors a few times a month fell from 71 percent to 54 percent, and those who reported doing favors for each other fell from 39 percent to 23 percent. According to a 1948 Gallup poll, 60 percent of adults surveyed that year reported borrowing and lending items with neighbors, and 70 percent reported having neighbors over to their house. In that same year shortly after World War II, nearly 50 percent reported doing shopping for neighbors and 40 percent said they looked after each other’s children.

But one big driver of these changes is trust, and between 1970 and 2018, polls show the percentage of Americans who agree that “most people can be trusted” has also plummeted to single digits in some cases.

That’s the difference two generations can make. Keep in mind, the folks polled in 1948 were the same Americans who posted 90 percent church membership rates.

And while 70 percent of Americans identify as Christian in 2020, the actual share of adults reporting they attend weekly church services fell from 57 percent to 42 percent between 1972 and 2018. This follows the downward trend in marriage, with non-married adults now representing a majority of Americans, and the observed fact that married families tend to go to church more frequently than singles.

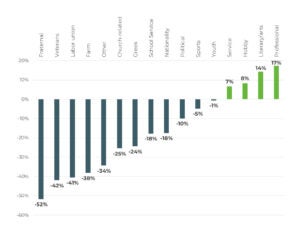

But it’s not just churches. Between 1974 and 2004, membership in voluntary organizations such as fraternal, veterans, and labor unions, fell from 75 percent to 62 percent, with fraternal organizations dropping a whopping 52 percent.

In the U.S., the Freemasons, one of the oldest fraternal organizations in the country and one that counts numerous Constitution signers and past presidents, tells the tale with its numbers. If the American landscape is lined with churches, then lodges with the sign F&AM are the dots. But consider that in 1924, the Freemasons counted 3 million members, with 4.1 million at the group’s high point in 1959. By 2000 the membership rolls had fallen to 1.8 million, and in 2019 to just 1,010,595. Meanwhile, the nation’s population in 1924 was 114 million, compared to 2020’s 330 million.

A more virtual world

If you’re a rural American, you understand the relationship between family farms, churches, and social clubs like the Masons, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Rotary. In a small town, the members are the same group of neighbors. But as the nation has advanced technologically and small-town employers have been gobbled with conglomerates, so it seems has participation in these organizations. Online connectivity meanwhile has never been higher. The online community LinkedIn reports 900 million members, with social media site Facebook logging 3 billion users a month. And the same is true with online church services, which bring in millions of viewers weekly.

For my part, I currently serve as chair of our pastor/parish committee at Prairie City United Methodist Church, am a Past Master at Centerpoint F&AM Lodge 597, on the board for our Clay County Optimist Club and was recently awarded the Meritorious Service Award at the Scottish Rite. My church, like so many other rural congregations, has gone from average weekly attendances of 30ish in the 1990s when I was a kid, to anywhere from five to 10. Whereas we once had our own minister, we now share a pastoral team with four other churches, and I serve as a lay speaker when needed.

The question of increasing active membership is the same there as it is back at the lodge, and every other lodge, where membership numbers are comparable to the national trends. Whether at an Optimist Club breakfast or a church dinner, at the ripe old age of 48, I’m the baby of the bunch, a full generation younger than the other members.

But while attending each of these meetings, the members seem focused on the trends involved in their own group as opposed to the larger phenomenon of de-grouping, even though these members all double as participants in the very same organizations I do. They like to blame partisan politics, from both sides, at each stop. Meanwhile, our Masons go to churches much like mine, and either belong to American Legions or Rotary, not unlike the Optimists. They do seem to notice that members of my generation are physically missing from the community though. Out of 286 graduates in my high school class of 1993, maybe a couple dozen still live in the area. Those are their kids. That said, we’re all friends on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Still together virtually, but not physically.

To the extent that religion and rural America blend together like the corn in fields, what affects one will most certainly be affect the other. While many writers attribute the dissipating attendance in services and drop in overall identification percentages to political issues, it would seem that a broader look at the picture shows a trend toward disassociation from organized groups in favor of Internet activity.

What this bodes for the future remains unclear, but as de Tocqueville noted nearly 200 years ago, the desire to freely assemble is part of the nation’s fabric. But that assembly does seem to be trending toward the online and away from in-person.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana. You can see more of his work at the Boyce Group homepage.