Does a food label wording falsely coax you into thinking something is healthier for you? Sure, lots of them do. That’s the ‘healthy halo’ effect in marketing.

The grocery store can be quite overwhelming with the abundance of choices nowadays, and it can be difficult to spot marketing terms on food packages that consciously or subconsciously cause you to choose one product over another. “Healthy halo” terms are those that cause the consumer to believe that the product is healthier when in reality the term actually tells you nothing about the nutrition of the product. Aside from the statement of identity that lets you know what the food is, the information on the principal display panel of food packages isn’t particularly helpful and, in fact, most of it is just marketing.

So, here are five common “healthy halo” buzzwords to look out for.

1) Clean

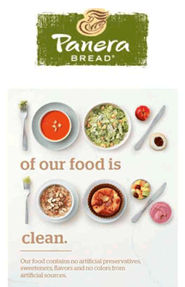

This one is prevalent not only on packaged foods, but also in commercials for restaurants like Panera and on social media.

Everything from “clean ingredients” to “clean food” to describing your diet as “clean eating” and even going as far as to describe your entire lifestyle as “clean living” are plastered all over some of the most popular social media influencers pages. So, what does it mean? Great question! It can mean whatever you want it to mean. It has absolutely no scientific or practical meaning unless describing the amount of dirt on your freshly picked veggies or food that fell on the floor. It’s a meaningless term when describing food, diet or lifestyle.

Assigning the term “clean” to food, diet and lifestyle implies that the alternative is “dirty” or “bad” or “unhealthy,” but when it’s not even defined or based on science in the first place, it really doesn’t tell you anything helpful. What it does do though, is make consumers believe that it must be safer or healthier if being described as “clean.”

Let’s take a look at Panera’s definition in the ad above. They define “clean food” as containing “no artificial preservatives, sweeteners, flavors and no colors from artificial sources.” In no way do these rules make their food safer or more nutritious than the same foods that may contain artificial ingredients. This is purely an appeal to nature argument, which is the logical fallacy that because something is “natural” it is therefore better or more nutritious or safer, but that is not an evidence-based argument. Which leads us into the next “healthy halo” buzzword.

2) Natural

This one is on food packages everywhere. It’s not formally defined by the FDA, although they do have a longstanding policy concerning the use of “natural” in human food labeling. The FDA has considered the term “natural” to mean that “nothing artificial or synthetic (including all color additives regardless of source) has been included in, or has been added to, a food that would not normally be expected to be in that food.” Well, that looks very similar to Panera’s definition of “clean.”

So, does it mean anything in terms of the safety or the nutrition of the product? No. Again, this is purely an appeal to natural argument. Many consumers assume that natural equates to more nutritious or safer, but that’s just not the case. In fact, food additives such as preservatives, which many would not consider to be “natural” can actually make food safer. I’ve written about food additives such as flavors and colors here. Swapping out artificial colors and flavors for natural colors and flavors does not make the product any safer or more nutritious. Many companies, even Butterfinger, have jumped on this marketing trend and reformulated their products to contain “no artificial flavors or colors,” arguably making the product much worse from a taste perspective (just my opinion of the new and not improved Butterfinger recipe). Some products, such as Trix, have even reverted back to their old formula after consumers became unhappy with the changes.

3) Superfood

What does superfood mean? I don’t know, you tell me! Any answer could be true as this is yet another unregulated marketing term that makes the consumer believe they’re getting some sort of disease fighting, antioxidant packed food.

When you have terms like this that have no formal regulation for food labeling or scientific basis, they can be used for any product and in any way the marketer wants. Although it may be true that foods labeled as “superfoods” meet the Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of “rich in compounds (such as antioxidants, fiber, or fatty acids) considered beneficial to a person’s health,” in reality, no one single food is going to live up to the disease fighting claims that are attributed to “superfoods.” Perhaps the only thing super about “superfoods” is the boost in sales that follows after slapping a “superfood” label on a product.

According to Mintel research, in 2015 there was a 36 percent increase globally in the number of foods and beverages launched that were labeled as a “superfood,” “superfruit,” or “supergrain,” with the United States leading those product launches. Sensationalized superfoods including blueberries, acai, avocados and almonds may be nutritious and a great addition to an overall healthy, balanced and varied diet, but there are many other equally nutritious and potentially less expensive options that shouldn’t be overlooked just because they don’t carry the “superfood” healthy halo.

4) ‘Real’ food or ‘Made with real ingredients’

Ok, this one may just be the most meaningless of them all. I don’t really have that much to say about this one except, what are all of the other ingredients and foods if only some are considered to be “real?” Like “clean” and “natural,” this goes back to the appeal to nature fallacy. “Real” implies natural and unprocessed, which implies safer or more nutritious, but hopefully you are well aware now that natural being safer or more nutritious is not the case.

Oftentimes, stating “real food” is used as a way to compare one product to a similar product and to essentially claim superiority over a competing product even though they will obviously both contain real food and real ingredients. KIND bar has used this marketing approach for their protein bars, which are, in fact, made from real food like literally all other protein bars.

5) No toxic chemicals

Recently both Stonyfield and Nature Valley have taken this marketing trend to the bank with some pretty ridiculous fearmongering campaigns as I’ve posted about here and here. Organic Valley took it a step further and put a “never toxic pesticides” label on its newest ultrafiltered milk. However, “toxic pesticides” is a nonsense phrase. There is no such thing as a “toxic chemical,” there are only toxic doses. The phrase “the dose makes the poison” applies to all chemicals, both natural and synthetic. Every chemical, even water, can be toxic at a given dose.

No food — organic or otherwise — contains a “toxic” level of pesticides, and organic farming uses pesticides of which have overlapping toxicities to those of synthetic pesticides. The organic industry has done an excellent job of misinforming consumers about conventional foods and positioning organic as safer and healthier even though this is not the case. This is just another attempt to scare consumers over equally-as-safe conventional milk in order to get them to pay more for the organic versions. Food additives and pesticides are regulated to ensure that there are no toxic levels of any chemicals in food products.

Unfortunately, consumers will continue to be misinformed and misled by marketing campaigns and trendy buzzwords. The best thing to do is to just skip over the marketing labels and look at the factual information located on the back of the food package, such as the nutrition information and the ingredients and allergens. The rest is mostly just fluff with no real scientific basis.

Food Science Babe is the pseudonym of an agvocate and writer who focuses specifically on the science behind our food. She has a degree in chemical engineering and has worked in the food industry for more than decade, both in the conventional and in the natural/organic sectors.