Even with some regions recently drenched, the newest American Farm Bureau Federation drought survey shows there is still a long road to recovery. Sixty percent of the American West, Southwest, and Central Plains have been categorized as a D1 (moderate) drought or higher, putting agricultural production and commodities at risk, while threatening to impact consumers with increased prices and scarcity of goods.

This survey serves as the fourth survey conducted by AFBF to evaluate drought’s impact on farms and ranches. The survey was conducted between Oct. 19 and Dec. 13 to quantify ground-level drought impacts, including demographic questions to help distinguish state affiliation, crop and livestock-specific factors, and general water access.

In total, 16 states, including and north of Texas, up along the Plains to North Dakota, and west to California were surveyed to include 550 responses. These states provide nearly half of the nation’s $364 billion production by value, including 74 percent of beef cattle, 50 percent of dairy production, and 80 percent of wheat production, all by value, according to the AFBF.

Crop yields experienced wide-reaching reduction

While yields are likely to experience reduction, the number of farmers intending to switch crops or till under crops has dropped back slightly since the summer 2022 results. Marginally improved moisture in parts of the West have provided contrasting conditions to a year ago.

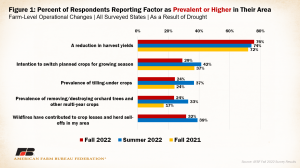

Out of the 550 responses, 76 percent rated a reduction in harvest yields due to drought as prevalent or higher in their area. This was slightly higher than the summer 2022 results (74 percent), and the fall 2021 results (72 percent).

Respondents anticipate that average crop yields will be down 44 percent in 2022 because of drought conditions, with the largest drop expected in Texas (down 66 percent), followed by Kansas (down 63 percent), and Nevada (down 60 percent).

One Pinal County, Arizona, farmer responded, “Unable to plant cotton, didn’t have enough water for barley, should have eight-10 cuttings of alfalfa by now but only have one.”

Surveyed respondents also indicated that 29 percent intended to switch planned crops for the growing season due to drought. This is a smaller number than the 42 percent this past summer, and 37 percent in the fall of 2021. The number of respondents who reported removing orchard trees and multi-year crops is down from the 33 percent reported in the summer 2022 survey.

According to AFBF, a survey respondent from Sutter County, California, commented, “Many orchards are being removed. There are also substantially fewer rice acres farmed in our area due to lack of water.”

While tillage and crop removal numbers have decreased, this may be due to farmers already having removed these crops earlier in the year.

Crop yields have impacts beyond the planted crops

AFBF lists apiaries and honeybees as one of the implications of diminished crop yields. Reduced water and plant production will go hand-in-hand with reducing pollination activity and honey crops.

One Shasta County, Cal., farmer wrote, “Our land no longer has water, so our bees have lost their grazing land. We haul water to all of our locations. Have not made a honey crop, instead we are feeding with costs up to $100,000 and more this year alone.”

Another concern for farmers in certain areas are the reduced soil health and long-term productivity. A Cheyenne County, Colorado, farmer said, “We are experiencing continued soil moisture depletion, no perceptible recharge. Soil surface becoming powdery and more fields experiencing blowing soil during high winds.”

In contrast, California has been recently inundated with rain that occurred after the survey data collection. Flooding has delayed harvests, and damaged crops. In Salinas Valley, where more than half the nation’s lettuce and leafy greens are produced, rains have delayed land preparation and planting procedures. Planting delays may also impact global markets and consumers already facing volatile food prices.

Livestock production affected by droughts

Eighty-nine percent of survey respondents reported an increase in local feed costs as prevalent or higher, down just one point from the summer 2022 results. Reductions in herds dropped three percent from previous results to 33 percent in surveyed regions. The largest herd decline remains in Texas (46 percent), followed by Nevada (45 percent), and Arkansas (35 percent).

Feed prices and poor-quality forage will likely cut into operational income, along with potentially affecting livestock performance. In Duchesne County, Utah, a rancher responded, “Currently, our pasture conditions are poor, but we have sufficient hay to feed from Dec. 1 through May 1, provided snow cover allows grazing. With the forecast of at least six more months of La Nina, and the result being another light or dry winter, further cuts may be necessary. Our calf weights are down from mid-500 lbs. calves by mid-October each year to mid- to upper-400 lbs. calves in mid-October in 2021 and 2022. That is approximately a 10-15 percent loss in calf weights because of drought.”

Public lands ranchers in the West are also being hard-hit. Forty-two percent of respondents reported impaired use of public lands (down 57 percent from summer 2022), and 71 percent reported removing animals from rangeland due to insufficient forage.

In the summer of 2022, 67 percent or respondents reported reducing herd sizes in 2021. And over half were further reducing during 2022. Smaller inventories of livestock across the West, a region that supports over 70 percent of domestic beef production by value will decrease supply and drive up prices for consumers.

Reduced surface water deliveries are widespread

Over 60 percent of respondents have continued to report increased use of groundwater resources. However, many farmers find new wells are cost-prohibited or cannot be drilled because of regulations, or salinity in the area. Respondents reported that the cost of drilling a well is up over 100 percent.

A Pinal County, Arizona, farmer described, “We cannot drill a well and have to pay a water assessment annually that is attached to our taxes even if there is no water available. This year the water portion was over $19,000. We are also not permitted to drill a well in our water district. The district is drilling a few wells to add to the surface water, but that water will not make it to our farm as the wells are too far away.”